How Clark Griswold destroyed John Carpenter’s dark Sci-Fi thriller – The story of Memoirs of an Invisible Man

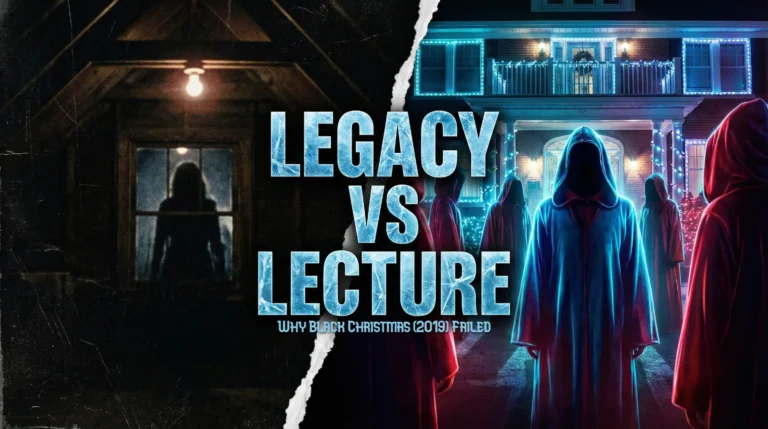

Welcome to Knockout Horror. We are one day away from December. Christmas is creeping up like a masked killer in a slasher movie, just waiting to bash you around the head with festive cheer. To get into the spirit, I wanted to spend a little time today talking about what happened when a comedy legend clashed heads with a horror master. Let’s take a look at how Clark Griswold destroyed John Carpenter’s Sci-Fi Thriller.

“🎶It’s that time, Christmas time is here! Everybody knows there’s not a better time of year“. These words sound a lot like an honest depiction of love for the festive season; a time of the year that I do really enjoy. The more Xmas movie-literate readers, however, will recognise those lines as being from the opening verse to Mavis Staples’ Christmas Vacation.

Highlights

One of the greatest Christmas movies of all time

As soon as December rolls around, there is one movie that is an absolutely essential watch but it is most definitely not a horror film. It’s the holiday classic National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. I first watched this movie back when I was around 10 years old. I’m not going to lie, at the time I felt a little bit rug-pulled.

That opening animated segment featuring a bumbling Santa Claus having an absolute nightmare while attempting to drop off presents at the Griswold residence had me fooled. When those grainy live action shots of the family heading out to find their perfect Christmas tree in the ol’ front wheel drive sleigh kicked in, I felt duped.

What the hell was this? This isn’t what I signed up for. It only took about two minutes for me to be hooked right back in, though. Chevy Chase and Beverly D’Angelo hitting that pitch perfect “Fa-la-la-la-la, la-la-la-la” after Rusty refused to join in on the singing had me creased up in fits of laughter.

I still, to this day, think that National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation is among the greatest Christmas movies of all time. It’s side-splittingly funny, absolutely relentless when it comes to the laughs, and actually quite touching in parts. When it comes to warm and cosy Christmas comfort food viewing, few films can beat it.

We could write an entire article about that movie’s troubled development but this is a horror website, not a Christmas website. Suffice to say, the film’s lead star was as combustible as he was brilliant. Few actors shared the level of comedic talent required to bring a character like Clark Griswold to life. But with that talent came an abundance of insecurity.

An iconic and beloved comedy character

Clark Griswold has become something of a cinema icon thanks to the Vacation movies. His earnest optimism, bumbling social awkwardness, and the constant chaos that surrounds him makes him one of the most memorable protagonists in comedy history. And let’s be honest, his legendary, wide-eyed meltdowns when the pressure finally gets too much are the moments that make him truly hilarious.

He’s just such a weirdly lovable character. Sure, he messes things up, is massively over-ambitious, and doesn’t always think things through. But there is an honesty and innocence to him that is impossible not to appreciate. He adores his family and every single one of his whacky ideas is purely centred around spending time with them, creating memories, and making them happy.

Behind that lovable character was a man that was, perhaps, one of the greatest cinema comedy actors of his era – Chevy Chase. Chase had a knack for physical comedy that few performers shared. His timing was impeccable and he turned every single second of camera time into a visual treat.

Whether through impressively effective slapstick prat-falls and bumbling awkwardness or through wild-eyed facial expressions and looks of bewilderment; Chase was going to make sure that he was the centre of attention at all times. He was brilliant and that is a fact that is often buried in the modern era for one very specific reason – Chevy Chase is an incredibly difficult and controversial person.

That’s a complete understatement!

To be honest, that’s putting it lightly; by most accounts, he’s a complete twat. Whether it’s allegations of physical violence, misogyny, racism, problems on set, or just his generally hostile demeanor. Finding co-stars who have nice things to say about Chase is a very difficult task indeed.

In fact, his difficult personality caused problems on the set of Christmas Vacation before the movie had even started filming. The, at the time, struggling and desperate for work filmmaker Chris Columbus was signed on to direct but threw in the towel almost immediately after sharing dinner with Chevy Chase:

We spent two hours together … I left the dinner … I thought, ‘There’s no way I can make a movie with this guy’. src

That’s a director who thoroughly believed his career was over and considered himself lucky to be offered this job. Turning down Christmas Vacation felt like the final nail in the coffin of his career but he simply couldn’t see himself working with Chase.

That’s a stark indicator of just how difficult this man was. Luckily for Columbus, his good friend John Hughes respected him for his honesty. He pivoted, offering him the director’s seat on another holiday classic, Home Alone, and the rest is history.

Regarding his reputation, Chase, in a very on-trend fashion, remarks “I don’t give a crap!”. Unfortunately, for all his talent, Chevy Chase firmly believed his own hype. He considered himself to be of the utmost importance, utterly irreplaceable, and impervious to criticism. He also seemed to believe he was immune to the whims of a very fickle Hollywood. Reality was about to catch up with him.

Clark Griswold meets a master of horror

By the late 80s and early 90s, Hollywood was changing. The slapstick, star-centric comedy that made Chevy Chase a household name in the 70s and 80s had suddenly become passe. Thanks to Chase’s volatile reputation and increasingly tepid responses from both critics and audiences, starring roles were becoming more difficult to come by.

Chase knew that he needed to make a change. He was bored of being the funny guy and decided that he would be better served by pivoting towards serious roles. That begs the question, what happens when Clark Griswold suddenly decides he wants to be the next Cary Grant?

Well, in this case, he buys the rights to a serious sci-fi novel, demands a serious director, and effectively walks a horror legend right off a cliff. Enter John Carpenter and the disaster that was Memoirs of an Invisible Man.

By 1992, Carpenter was already making his mark as a future legend of horror. He effectively created the slasher genre with 1978’s Halloween. He then followed that up with The Fog, and even directed one of the greatest horror movies of all time – The Thing. Of course, that movie was a box-office bomb and widely panned on release. A fact which plays into this story in a big way.

The box-office bomb that changed a career

While it would go onto receive extraordinarily positive critical re-appraisal in later years, The Thing’s failure lead Carpenter to an extremely low point in his once stellar career. Big studios didn’t want to work with him, anymore. He was considered to be too weird, too dark, and too risky.

This lack of success forced Carpenter to sign on to direct movies that would, otherwise, be beneath him. Some of these films, despite being commercial flops, went on to be cult classics – Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), They Live (1988). But they were not the big name projects he envisioned himself making and they simply didn’t make money.

This is where Memoirs of an Invisible Man comes in. This movie was, ostensibly, a Chevy Chase vanity project. This was how he was going to revive his career and change the way studios, and Hollywood, perceived him. He would no longer be the bumbling Clark Griswold. His days of falling off of ladders and nailing his glove to the house were over. Instead, he was going to be a tall, suave, and handsome leading man.

The tone was set, the stars were in place, and all it needed was a director. Ivan Reitman (of Ghostbusters fame) was attached to the project along with screenwriter William Goldman (Misery (1990)) and they had one simple idea – let’s make it a broad comedy. Basically, Clark Griswold somehow turns invisible for the lack of a better way to describe it.

Reitman had struck gold with Ghostbusters and knew exactly what audiences wanted to see. He had the perfect concept to make the most of Chase’s unique qualities as a comedic performer.

There was just one small (huge) problem…

There was one problem, Chase absolutely hated the idea. He wanted a much darker movie with a philosophical bent that focused on the loneliness of invisibility. He wanted the movie adaptation to follow the tone of the original H.F. Saint novel. After all, this is what attracted Chase to the property.

Remember, this was his project and his chance to show his dramatic acting chops. He thoroughly believed that this was his ticket to the Hollywood A-list. It was going to be his way or the highway. Reitman and Chase clashed so much that Reitman gave Warner Bros an ultimatum “either he goes, or I go”.

Chase, still holding onto the dregs of his 70s and 80s stardom, had massive sway with the studio. They sided with Chase and so Reitman walked. This opened the door for a director who was even more poorly matched up with Chase’s vision – John Carpenter.

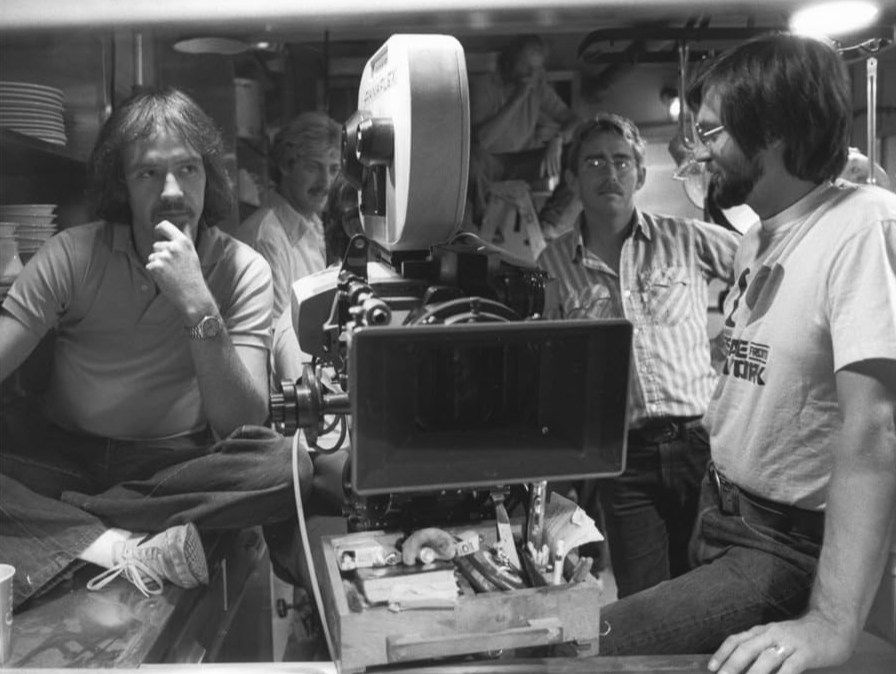

Carpenter, quite frankly, needed to work to pay the bills. He didn’t receive many big-budget movie offers and was swayed by the chance to work with special effects, again. Carpenter has described himself as being in survival mode. Signing on to direct Memoirs of an Invisible Man is a perfect example of this.

Enter the Master of Horror (Reluctantly)

Carpenter stepped into this production, not as a passionate auteur with a burning desire to tell this story but, essentially as a high-end gun for hire. He took the job because it was a studio picture with a decent budget. It also offered him the chance to work with Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) on some potentially ground-breaking VFX.

He wasn’t there to make friends; he was there to make a sleek, Hitchcockian sci-fi thriller. Unfortunately, he walked straight into the active minefield that was Chevy Chase and an antsy studio. Carpenter was a notoriously no-nonsense, blue collar director whose success came from knuckling down and getting the job done. Chevy Chase was, to put it lightly, an absolute diva.

Constantly desperate to look cool, completely unaware of his waning spotlight, and wielding a huge amount of creative control. Chase was about to make Carpenter’s life hell. Carpenter had every intention of making a dark, noir-style, science fiction thriller. Chase just wanted to make sure the camera caught his best side.

Chase hated the heavy makeup needed for special effects and would rip it off before shooting had finished. Along with costar Darryl Hannah, who shared in his petulance and stubbornness, he was determined to make Carpenter’s work experience miserable. Carpenter, in later interviews, wouldn’t even address the pair by name. Instead choosing to refer to them as being like “your boss’s spoiled kids”.

On top of that, the studio were in an absolute panic that they had just spent millions of dollars funding a Chevy Chase movie that had no laughs. Numerous script rewrites were offered up to inject Griswold-isms into the film and keep the mood light. The result was a tonal mess of a movie that had absolutely no idea what it wanted to be.

Pushing and Pulling

Just about everything in this movie clashed. The studio wanted it to be a witty film with some great slapstick laughs and a clever story. Carpenter, on the other hand, wanted lots of gritty tension, intense chase scenes, and high-stakes espionage. The two themes were like chalk and cheese.

Just take the sequence where Chevy Chase’s character tries to evade government agents as an example. It combines stealthy tension with pratfalls and awkward physical comedy, making it feel incredibly uneven. Critics and audiences had no idea whether they were supposed to laugh or be on the edge of their seats.

On top of this, Chase had his own very specific idea about who he wanted the lead character, Nick Halloway, to be. Chase believed Nick should be a charming, self-deprecating, and romantic character. Carpenter, on the other hand, believed he should be subtle and realistic, reacting to the events taking place around him. This caused the pair to clash mercilessly.

While Carpenter was trying to put the focus on paranoia and the existential reality of being invisible, Chase was more interested in portraying a romance with Daryl Hannah’s Alice Monroe. That’s without mentioning Chase’s inability to suppress his comedic-leanings causing him to inadvertently inject humour into numerous scenes.

It was a tonal tug of war. The suspense fought the comedy, the comedy fought the suspense, and the romance felt massively out of place. Carpenter famously stated later that Chase tried to direct him, telling the horror master how to shoot scenes. You can imagine how well that went down with the guy who made The Thing and Halloween. It feels like the lead actor is starring in a completely different film from the one being directed.

When Clark Griswold got serious

One of the most understated problems with Memoirs of an Invisible Man isn’t necessarily the script or the direction; it’s the sheer cognitive dissonance of watching Chevy Chase trying to be a serious romantic lead. It creates a sort of cinematic uncanny valley. You are looking at a human face that you recognise, but the behaviour is so alien to what your brain expects that it just feels… wrong.

It’s kind of hard to describe. It’s like trying on a much smaller version of a comfy piece of clothing that you really love. Sure, it’s familiar and you still like it but it doesn’t fit and is horribly uncomfortable. Chase felt incredibly out of place in this role.

Remember how I mentioned earlier that Chevy Chase wanted every single bit of attention whenever he was on screen? Much of this attention was achieved by simple physical ticks, expert use of facial expressions, and a constant need to be doing something funny.

By 1992, audiences had spent nearly two decades being conditioned to laugh the moment Chase walked into a frame. You were literally waiting with baited breath for him to do something hilarious. He was the guy who tripped over podiums, the guy who got his tie stuck in the shredder, the guy who strapped a dead aunt to the roof of a station wagon. That was all gone.

Serious Chevy Chase just doesn’t work!

When he appears on screen here, playing Nick Halloway as a weary, cynical stock analyst, you spend the first twenty minutes waiting for the punchline. You are waiting for him to fall down a manhole or make a snarky comment to the camera. But the punchline never comes.

Instead, we get a performance that Chase clearly intended to be “understated” and “cool,” but actually comes across as simply a little bit cringe-inducing. In his desperate attempt to strip away the “Griswold-isms” and be taken seriously, he stripped away all the charisma that made him a star in the first place. Without those traits, he was just an actor who wasn’t as believable, as handsome, or as capable as other Hollywood leading men.

He sleepwalks through the movie with a flat, monotonous delivery that sucks the energy out of every scene. Watching him try to romance Daryl Hannah isn’t sweeping or tragic; it’s just really damn awkward. It feels like watching a clown trying to perform Hamlet without taking off the greasepaint first. You can’t focus on the tragedy because you’re too busy wondering where the honking horn is.

It effectively breaks the movie in a very specific way. A thriller relies on tension and you can’t build tension when the audience is subconsciously suppressing a giggle every time the protagonist opens his mouth. The ghost of Clark Griswold haunts every frame of this film, arguably more than the invisible man himself.

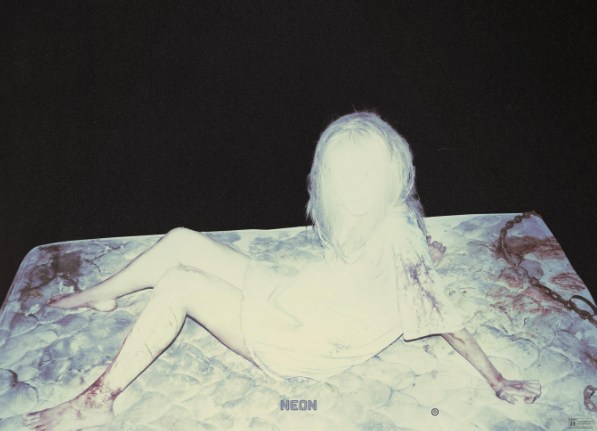

The saving grace of the invisible man

If Chevy Chase’s performance is the black hole sucking the life out of this movie, the special effects are the supernova trying their very best to illuminate it. It absolutely has to be mentioned; visually, Memoirs of an Invisible Man is absolutely stunning. You can clearly see why Carpenter was so eager to work with ILM.

While the script was busy having an identity crisis, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) were quietly revolutionising the way visual effects were handled on screen. Let’s get some perspective for a second here, as well. This was 1992… Jurassic Park was another year away. We were still in the era of Spielberg trying to make magic with a mechanical monster that was not-so-affectionately dubbed “the Great White Turd” in Jaws.

We weren’t in the era of “fix it in post” or “add a bit of CGI”. Everything had to be practical or made using camera trickery. What Carpenter and ILM achieved here was a masterful blend of early digital technology, optical illusions, and good old-fashioned practical effects.

The scene where Nick’s body is outlined by rain is kinda mind-blowing, especially for a kid who grew up in the 90s. It’s a moment of pure visual poetry that feels like it belongs in a much better movie. Then there is the scene where he inhales smoke to outline his lungs, or the moment he applies makeup to create a floating, hollow face. It’s frankly incredible what they achieved.

These effects don’t just look “good for the 90s”; this isn’t a case of gritting your teeth a little at how awkward parts of An American Werewolf in London look nowadays. They hold up remarkably well today because they have a tactile weight to them that modern CGI often lacks. Movies like this are why people complain about the lack of practical effects usage in modern film.

A testament to the skill of one of horror’s greatest directors

Memoirs of an Invisible Man is also a testament to John Carpenter’s professionalism. By all accounts, he was miserable making this film, as you can probably imagine. He was dealing with a studio breathing down his neck and a lead actor who was trying to tell him how to direct. Here’s a quote from Carpenter where he doesn’t drop names but is clearly talking about Chase:

“Let’s just say there were personalities on that film… he shall not be named who needs to be killed. No, no, no, that’s terrible. He needs to be set on fire.”

Imagine making a movie as groundbreaking as Halloween or as important as The Thing (even if people didn’t realise it at the time) and then coming to work everyday to deal with that. A lesser director might have phoned it in, pointed the camera, and collected the cheque.

Carpenter didn’t. He shot the hell out of this movie just as he did with every other movie he ever made. He framed it with that classic gorgeous Carpenter wide-screen composition, using shadow and light to sell the illusion of emptiness. It still looks great to this day.

He might not have cared about the character of Nick Halloway a whole lot, but he clearly cared about the craft of cinema. It’s just a shame that all this technical wizardry was expended on a Chevy Chase vanity project that nobody asked for.

Critical Confusion and the career nosedive

When Memoirs of an Invisible Man finally materialised in theatres in February 1992, the reaction was… well, very visible… It was visible confusion. Warner Bros. had no idea how to market it (the trailer made it look like a zany comedy which it absolutely wasn’t), and audiences had no idea how to watch it or how they should be taking it.

Critics were largely merciless, as you can probably guess. While some praised the special effects, the majority just couldn’t get past the tonal identity crisis. The Washington Post called the plot “lazy,” and many reviews pointed out the exact same thing we’ve been discussing: it is impossible to watch Chevy Chase in a serious role without waiting for him to fall over or pull a stupid face.

The box office numbers were the final nail in the coffin. It bombed, hard. For John Carpenter, this was yet another bruising defeat that pushed him further away from the big studio system and back towards independent financing. But for Chevy Chase? It was an absolute catastrophe. This was, honestly, the beginning of a slide that would last decades.

This movie was supposed to be his pivot. This was meant to be the moment he graduated from Saturday Night Live alumnus to serious, dramatic heavyweight. Instead, the failure of Memoirs sent him spiraling back into the embrace of the very type of roles he had tried to escape. Typecasting suddenly became a safety net for him.

Chevy Chase’s last attempt at glory

In the years that followed, Chase didn’t just flounder; he arguably tanked. He hid behind generic family comedies like Cops & Robbersons and Man of the House. These were movies that felt tired, cynical, and a million miles away from his glory days.

He eventually tried to go back to the well with Vegas Vacation in 1997, but by then, the magic was gone. The Clark Griswold charm had curdled and nobody cared anymore. The irony is palpable: in his desperate attempt to kill off Clark Griswold and become a serious star, Chase essentially rendered himself invisible to Hollywood for the better part of two decades.

He popped up every now and then, often in really surprising places. Commercials, a bit part in Hot Tub Time Machine, kid’s movies like Snow Day. I occasionally see him returning to his festive roots in daytime Christmas movies, too.

It would never be the same, though. Memoirs of an Invisible Man marked the downturn of his career and a point of no return. His difficult reputation preceded him and his star had waned to the point of making the hassle far from worth it.

Look, I don’t want this to be a Chevy Chase hit piece, lord knows there are dozens of those. While it is probably correct to say that he was always complicated, it wasn’t always bad. There are moments of genuine decency by Chase that get completely buried under the cartoon villain narrative that he is painted in during recent years.

Playing Devil’s Advocate!

Chase was the first person to offer support to legendary comedian Norm Macdonald when he was fired from SNL for refusing to make jokes about O.J. Simpson. He told him he was the best thing on the show and to not let the network bastards grind him down.

Johnny Galecki, who starred as Rusty in Christmas Vacation and would go to huge success in Roseanne and The Big Bang Theory, was effusive about Chevy Chase as a costar. He said that he was a generous and patient mentor on set. He even took him around to different film sets to meet massive movie stars during lunch breaks.

Similarly, Michael Anthony Hall maintains that he still loves Chase, despite some ribbing on the set of National Lampoon’s Vacation. Vacation costar and onscreen wife Beverly D’Angelo has also maintained a life long friendship with the actor and loves him dearly.

He’s also shown a commitment to environmental activism that goes way beyond a convenient Hollywood photo-op. He has raised millions for environmental causes and education. He’s also maintained decades long friendships with people like Martin Short and Steve Martin who don’t exactly suffer fools gladly.

I think the really tragic thing about Chevy Chase and about Memoirs of an Invisible Man is that he is, perhaps, less a bad man and more a ruthlessly insecure man. He let his defense mechanisms impact this film and, indeed, his entire career. If Chase could just forget about being the smartest guy in the room and just focus on being the nicest, he would be a national treasure.

Final thoughts

I can’t think of too many actors who brought me so much joy while growing up. As soon as I saw his face, I knew I was in for a good time. Oh, and I also knew that I better be careful what I am eating because of the distinct possibility I would choke from laughing.

I still watch National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation multiple times every year. I still think Clark Griswold is one of the comedy world’s greatest characters, too. Only Chevy Chase could have brought that character to life the way he did. Chase would briefly revive his career in 2009 as Pierce Hawthorne in Dan Harmon’s Community. Unfortunately, old demons would raise their heads and that would end in disaster, too.

When it comes to John Carpenter, well, he would continue to solidify his reputation as one of the greatest horror directors of all time and a legend in his own right. Few filmmakers can stake a claim to so much importance to one genre.

Even Memoirs of an Invisible Man has gone on to gain a bit of a cult following. It turns out modern viewers enjoyed seeing Chevy Chase shedding the shackles of Clark Griswold. It kinda makes you think, what could have been? With a little more cohesion and a little less studio interference, perhaps his career as a serious actor could have worked.

I know this wasn’t exactly a horror themed article but I appreciate you making it to the end. Thanks for reading and spending your time at Knockout Horror.

Support the Site Knockout Horror is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. Basically, if you click a link to rent or buy a movie, we may earn a tiny commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This helps keep the lights on and the nightmares coming. Don't worry, we will never recommend a movie purely to generate clicks. If it's bad, we will tell you.

Disclaimer: All movie images, posters, video stills, and related media featured in this article are the property of their respective copyright holders. They are presented here under the principles of fair use for the purposes of commentary, criticism, and review. Knockout Horror makes no claim of ownership over these materials. Each image is used purely to illustrate discussion of the films and to provide context for readers. We encourage audiences to support the official releases of the movies mentioned.